(Click on images to enlarge.)

Growing up on Montgomery Street in Newark's Third Ward, I fondly

recall Newark's pioneer contributions to the early growth and evolution

of broadcast radio as America's primary family entertainment medium,

especially during the 1930's Depression era.

Three Newark-based radio stations were among the first one hundred

to broadcast in the first two years of commercial radio.1

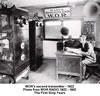

First Newark Radio Station

The first was WJZ which started broadcasting in Newark on October

1, 1921 as an experimental station of the Newark based Westinghouse

Electric Company.2

Its first broadcast studio and transmitter was located in the Westinghouse

meter plant at the corner of Plane and Orange Streets.

The studio occupied half of an upstairs ladies' restroom in the

Newark factory, a space measuring 15 feet by 30 feet. Microphones

and a control panel were installed and a few pieces of furniture

added, including a piano rented from the Griffith Piano Company.

Most of the entertainers were from New York and were brought to

the Newark studio by the Hudson Tubes (now Path) or the Pennsylvania

Railroad.3

Among the earliest entertainers on WJZ in late 1921 were Billy

Jones and Ernie Hare, later to become the best-known comedy act

in the early days of radio, and Paul Whiteman and his orchestra.

Newark radio station WJZ made broadcasting history in its first

year on the air by broadcasting a World Series game pitch by pitch,

getting the information by telephone.

WJZ's start of broadcasting in Newark on October 1, 1921 was just

10 months after America's first broadcast over KDKA in Pittsburgh,

on November 2, 1920.

Start-Up of America's First Station

The first broadcast of KDKA was held on election night, Nov. 2,

19204 from a 100

watt transmitter in a small makeshift shack on top of Westinghouse

manufacturing building in East Pittsburgh. The broadcast started

at 6 P. M. and continued until the following noon when Governor

James M. Cox conceded the election to Senator Warren G. Harding,

making him our nation's 29th president.

Start of WOR

Radio Station WOR was started by the Newark department store,

L. Bamberger & Co. with an investment of $20,000. It came on

the air in February, transmitting at 250 watts, as the nation's

sixth licensed radio station. Its broadcasting studio was in a corner

of the Market Street department store's radio and sporting goods

section. The "W" in WOR was a letter assigned to all Eastern

broadcasters. According to a station historian, the intention was

to obtain LB for the next two letters, making the call letters WLB

for Louis Bamberger. But WLB was taken, so the station engineer,

in Washington for that purpose, settled for whatever was next in

line. It was WOR. This set of call letters had been turned in the

previous day by Orient Lines and the "OR" could have stood

for ORient Lines.

The transmitter had been assembled in Bambergers by a salesman

in the radio department whose specialty was selling crystal sets.

When it failed to work, an experienced radio engineer from the Weston

Instrument Corp. on Frelinghuysen Avenue, W. Nelson Goodwin, Jr.,

was called in to help. Goodwin redesigned and rebuilt the transmitter,

and got it into working order, enabling WOR to come on the air.

In April 1923, at a meeting of the Board of Directors of L. Bamberger

& Co., they jointly recommended that, although WOR had been an

interesting adventure for the store's radio department, they did not

see much future for WOR as an advertising medium and recommended that

the WOR broadcast license be turned back in. The station's chief engineer,

Jack Poppele, at that meeting, convinced the Board to change their

minds and continue broadcasting from the department store site.5

In 1929, WOR now occupied larger broadcasting studios on the ninth

floor of Bamberger's--a non-selling floor--and it joined with stations

in Chicago, Cincinnati, and Detroit to form the Mutual Broadcasting

System. (By 1952, the Mutual Broadcasting System had 560 stations).

On February 23, 2002, WOR celebrated its 80th year of continuous

broadcasting at broadcast frequency 710.

Start of WHBI

WHBI, located in the Hoyt Brothers factory on Shipman Street,

was licensed on March 11, 1922, the month following Bamberger's

start-up.

The 'HBI' in the call letters WHBI stood for the station's sponsors

"Hoyt Brothers Incorporated." Its location in a factory

building was on Shipman Street, one block below High Street, and

running from Court Street to Springfield Avenue. At Springfield

Avenue, Shipman Street is a stone's throw from Gutzon Borglum's

Abraham Lincoln statue, the Civil War President seated on a bench

at the foot of the Essex Count Court House steps. (Borglum would

later do a larger carving of Lincoln on Mount Rushmore).

Life of WNJ: "The Voice of Newark"

WNJ at 1450 AM originally went on the air as WRAZ in June 1923.

It was the creation of Herman Lubinsky, a former naval radio operator,

who ran it from his radio shop at 58 Market Street. The call letters

"WNJ" were assigned in October 1924 and stood for "Wireless

New Jersey."

As WNJ, the station was initially located in the attic of Lubinsky's

home at 89 Lehigh Avenue. In 1925, Lubinsky built a studio at the

Paradise Ballroom in Newark.

In 1926, the station, now billing itself as "The Voice of

Newark" presented programming in Polish and Lithuanian, and

also broadcast home-produced dramatic hours featuring the WNJ players.

In 1928, WNJ moved its studio to the Hotel St. Francis in Newark

and continued operations from there until 1932, when the Federal

Radio Commission (FRC) denied WNJ a license renewal, forcing it

off the air.

Start of WNEW

When WNEW signed on to broadcast in 1934, it shared broadcast quarters

with WHBI in the Hoyt Brothers factory building on Shipman Street,

and at times shared the WHBI broadcast frequency.

The "NEW" in the station's call letters WNEW represented

that the station was a NEWark station, located in NEW Jersey, although

it eventually moved to New York City, as did WJZ.

Although WNEW first came on the air in 1934, it was not a new

station. It was a successor to Newark station WAAM which went on

the air April 10, 1922. WAAM merged with a Paterson station, WODA,

in 1933, but retained its 1130 frequency.

WNEW left the air January 4, 1993, when it was purchased by Bloomberg

Radio and its 1130 frequency became WBBR.

WVNJ -- The Newark Broadcasting Corporation

Another Newark radio station emerged on December 7, 1948 -- a powerful

5,000 watter at 620 on the AM dial. It was owned by The Newark Broadcasting

Corporation, founded by the Griffith Piano Corporation. Griffith

put the station on the air as a companion to their music business.

Programs originated from the window of the Griffith store at 45

Central Avenue. WVNJ broadcast a wide range of music styles, including

Latin rhythms in the evening.

WVNJ subsequently went through several changes of ownership, call

letters, and location. In 1985 as WSKQ with an all Spanish-language

format, it moved its transmitter and studios from Livingston to

New York City. It currently broadcasts at 620 from Jersey City as

WSNR, Sporting News Radio.

My Entry Into Radio

My entry into radio came in the late 1920s when, as part of a hobby

project in the YMHA hobby Shop on High Street, I built a crystal

set radio. It operated without an outside source of power, and you

located a transmitting station by scratching a piece of crystal

with a wire called a "cat's whisker".My crystal set was

in a cigar box and, I recall, I was able to get one station after

I managed to save enough money to buy a set of headphones and antenna

wire which I strung between chimneys on the flat tarpaper roof that

covered my home, No. 29 Montgomery Street and the attached adjoining

house, No. 31 Montgomery Street.

Life with Our First Family Radio

Our first family radio came sometime in the early 1930s. It was

a Majestic and it became a focal point of my home life afternoons

and for our family in the evening.

There were lots of afternoon serials for kids in the 1930s. I

especiallyremember Sherlock Holmes adventures sponsored by G. Washington

Coffee, the Witch's Tale, Chandu the Magician, and The Adventures

of Tom Mix. Mix had been a top star of movie Westerns in the silent

film era and the Tom Mix show was sponsored by Ralston Purina. Naturally,

our household cereal of choice was Ralston. It first aired in 1933.

The year 1933 also was the first year for The Lone Ranger, which

competed with Tom Mix and later won my preference. The Lone Ranger

ran for 20 years.

Newark Bears Broadcasts

Sometimes I would listen to the broadcasts of the Newark Bears

International League baseball games from Ruppert Stadium on Wilson

Avenue in Down Neck, Newark on station WNEW.

The announcer, as I recall, was Earl Harper.6

I had been so enthralled with his vocal delivery that I onetime

vowed to myself that I would become a radio announcer just like

him when I grew up.

Many years later, sitting in the pressbox at Ruppert Stadium for

a sporting event, as a sports writer for the Star-Ledger, I chatted

with the dean of Newark's Western Union telegraphers, Ed Weinstein,

and I told him how Harper had influenced me.

Weinstein told me that, although Harper broadcast the Newark Bears

out-of-town games ,he never traveled with the team. Weinstein said

it was he, Weinstein who traveled with the Bears and with his telegraph

key sent back each play to an operator in the radio studio who handed

it to Harper, who then reconstructed the play by play broadcast

in the Newark studio , and made it sound like he was actually at

the games.

Childhood Encounters with Broadcasting

My childhood encounters with actual broadcasting in late 20s/early

30s:

1. A glimpse of the Gambling show around 1930 through the glass-doored

studio window while attending an early morning meeting of the Bamberger

Aero Club on the same floor.

2. Standing in front of a theatre on Market Street off Broad listening

to Announcer Ted Webb chanting "This is Ted Webb-Your Man on

the Street, Greeting You from in Front of Adams Beautiful Air Conditioned

Paramount in Downtown Newark." He would stop passers by and

ask for opinions on happenings of the day, on live radio.

Childhood Recollections of Other Radio Shows

Some other shows from my Newark childhood were of course John

Gambling with his program of exercises in the morning, aided by

a 3-piece orchestra. Also in the morning, I listened to a show called

"Allan Courtney and His Joymakers."

It opened with the show's theme song "Start the day with

a smile, and you'll never feel blue...a little sunshine makes your

life worthwhile...start the day with a smile."

Family Listening at Night

Nights, in our Montgomery Street railroad flat during our first

radio years was mostly a family affair. We sat in the living room

around the radio and listened to The Eddie Cantor Show7,

Burns and Allen, Amos and Andy, The Rise of the Goldbergs, the Lux

Radio Theatre, and Avalon Time with Red Skelton. (Avalon was a cigarette

brand).

I particularly enjoyed listening to Bing Crosby, who was at the

start of his career and sang for 15 minutes for Cremo Little Cigars.

His opening theme was "Blue of the Night."

At that time, Crosby was a relatively little-known crooner. He

would subsequently go on to make film history by winning the first

Academy award, and record over 1,600 songs that included the 30-million

plus all time record bestseller "White Christmas."

For news in our house, we favored H. V. Kaltenborn, whose brisk

staccato speaking voice gave us the news of the day. He was on daily

all through the 1930s, but it is my understanding that he was the

very first of the numerous radio journalists of that era, and the

only one worthy of memory.

On Friday nights, we listened to The Little Theatre Off Times

Square, with Dom Ameche and Cliff Severe.

The Castleberg Amateur Hour

On Monday nights, we would listen to the Castleberg Amateur Hour

on WHBI, sponsored by Castlebergs, a downtown Newark jewelry store

and showcasing Newark talent.

Newark's Castleberg Amateur Hour, as best as I can recall, preceded

the start of Major Bowes Amateur Hour--a network broadcast from

New York--that went on the air around 1935. The Major Bowes show

amateur winner on its September 8, 1935 show was "The Hoboken

Four" which had auditioned for the show under the name "Frank

Sinatra and the Flashes."

Lucky Strike Hit Parade

Saturday night radio did not loom big for me until I entered my

teenage years with the advent of the Lucky Strike Cigarettes Hit

Parade.

This was a show that surveyed a prior week's sales of sheet music,

phonograph records and jukebox paid selections and came up with

the 10 best songs of the week, which it played with a live orchestra

and varying vocalists.

The show first aired in 1935 and lasted 20 years. The first hit

parade band was the Mel Wilton band and the earliest vocalists were

GoGo Delys, Ken Thompson, Charles Carlisle and Loretta Lee. Frank

Sinatra would join the list of vocalists in 1939.

The top hits in 1935 were "Alone" from the Marx Brothers

movie, A Night at the Opera, "In a Little Gypsy Tearoom"

and "Red Sails in the Sunset." Each of the 3 was No. 1

for 16 weeks that year.

The words of hundreds of popular songs aired on the Hit Parade

stuck in my memory and, decades later, as a father of two young

sons, while motoring on long vacation trips, I recall playing a

song game with them. I would ask them to give me any word and I

would then sing a few bars from a once popular song that included

that word, recalling the words from Hit Parade song recollections.

Sunday Morning Kiddie Hour

Sunday mornings, we turned in The Horn and Hardart Kiddie Hour.

It was sponsored by an automat food chain in New York City, where

you fed nickels and quarters into slots to retrieve the food you

wished to eat in their cafeterias.

I still recall their opening theme: "Less work for mother...just

lend her a hand...less work for mother...then she'll understand...She's

your greatest treasure....so make her life a pleasure....less work

for mother dear."

After the Horn and Hardart Kiddie Hour, my parents would then

take over and turn the dial to "The Jewish Hour," a one

hour program in Yiddish, on radio station WEVD--a station named

after Eugene V. Debbs, a labor activist and five-time candidate

for the presidency between 1900 and 1920. The station was owned

by the Jewish Daily Forward newspaper--a Yiddish-language daily

in New York City which in the 1920s also printed a special Newark

edition.

Memorable Radio Commercials

Radio commercials and product advertising seems a lot catchier

in my childhood radio listening years as some of these example may

indicate:

* Who could ever forget Johnnie's "Call for Phil-leep Mah-Rees"

(Call for Philip Morris).

* Ipana for the Smile of Beauty...Sal Hapitica for the smile of

Health

* Lux Toilet Soap: The soap 9 out of 10 famous screen stars use

* Texaco "Fire Chief" Gasoline

* Lifebuoy Soap: It Stops B. O.

* Kodak Cameras: You Press the Button: We Do the Rest

* Carters Little Liver Pills

* Pepsodent: You'll wonder where the yellow went when you brush

your teeth with Pepsodent

* Phillips Milk of Magnesia" To help maintain proper bodily

functions

Make Believe Ballroom

By 1935, WNEW had left Newark for New York and became the affiliate

in New York of the American Broadcasting System.

Martin Block started with WNEW that year as an announcer. His

first major assignment was commentary of the ongoing Lindbergh kidnapping

trial in the Hunterdon County Courthouse in Flemington. It held

America's attention and was avidly followed by virtually every Newarker

owning a radio.

To make up for open time gaps during his trial commentaries, Block

'invented' his "Make Believe Ballroom."

His 'invention' was the start of the disc jockey era on radio.

The term 'disc jockey' was pinned on Block by Walter Winchell.

On Block's show, which he called "The Make Believe Ballroom,"

he pretended to be talking about live bands and performers and he

made it sound believable even though he was only playing phonograph

records.

The "Ballroom" made Block rich and famous. At one time

in the Depression 1930s he was reported to be earning in excess

of $500,000 a year. A big song hit of the early 1940s was "The

Make Believe Ballroom" recorded by Glenn Miller and the Modernaires.8

How WOR Made Radio History

WOR made radio history during its life in Newark in a number of

ways. One of the most notable was through an accident that created

WOR's best performer.

That performer was John B. Gambling. Gambling was a young British

recruit at the station, who started with WOR as an engineer in 1925.

He had been called in to substitute for an absent announcer to do

an early morning exercise class. His handling of the program was

a big hit and he remained in that spot long after he had given up

gymnastics and into retirement.

With the retirement of John B. Gambling in 1955, he was succeeded

on his show, then called "Rambling with Gambling" by his

son, John A., and subsequently, his grandson, John R. -- a dynasty

that ended in September of 2000 when John R. left WOR to end 75

continuous years of a "Gambling" show on WOR.

In the 2003 Guinness Book of World Records, "Rambling with

Gambling" was listed as the world's longest-running radio show.

John R. resurfaced in 2001 on WABC-AM in New York with, what else,

"The John Gambling Show," a program that was still airing

at the start of 2004.

Another historic happening at WOR in Newark, then called "The

Bamberger Broadcasting System", took place in January 1924

when a WOR announce helped guide the dirigible Shenandoah--adrift

and lost in a storm--back to its base at Lakehurst, New Jersey.

Uncle Don's Alleged Historic "Slip-Up"

A notable piece of radio history tied to WOR involved a much-beloved

radio personality, Don Carney, known to his thousands of kiddie

fans in the seven-state WOR listening area as "Uncle Don."

Uncle Don would start his program each evening by arriving in

an imaginary autogiro he called "Puddle Jumper."

His opening song, which follows, became known almost everywhere

in the WOR listening area:

Hello nephew, nieces too,

Mothers and daddies, how are you?

This is Uncle Don all set to go,

With a meeting on the ra-di-o!

We'll start off with a little song

To learn the words will not take long;

For they're as easy as easy can be,

So come on now and sing with me:

Hibbidy-Gits has-ha ring boree,

Sibonia Skividy, hi-lo-dee!

Honi-ko-doke with an ali-ka-zon,

Sing this song with your Uncle Don!

What happened that legendary evening in the 1930s followed the

end of one of his six-days-a-week kiddie programs of songs, jokes,

advice, birthday announcements, club news, and lots of commercials.

Carney thought he was off the air, and with a live microphone

still beamed to his doting kiddie listeners, he reportedly remarked

"There! I guess that'll hold the little bastards."

Radio legend has it Uncle Don was fired that day, disgraced beyond

redemption, lived out the rest of his life in obscurity, and died,

an impoverished drunk, several years later.

The Urban Legends Reference Page, and two other internet sources

state that the claim that Uncle Don was fired is clearly false ...

that Don Carney continued to broadcast, day in and day out, starting

in 1928 and ending only when he finally stepped down from daily

broadcasting in 1947.

His New York Times obituary referred to the "Bastards"

happening as a myth of the broadcasting industry.

However, a reader of this "Old Newark" memory, on 1/11/04,

made this claim. "RE: this historic slip-up, my husband personally

heard this remark by Uncle Don while listening to his show on a

weekday night, as a young boy, but said he never heard him on the

air again."

And yet one more contribution to Uncle Don's historic slip-up

which should more or less wrap up and confirm this historic radio

happening.

On March 8, 2004, Brad Stone, from Morgantownn, Indiana, sent

me this comment:

"I can confirm that Uncle Don did, indeed say "There!

I guess that'll hold the little bastards."

"I have a 1970s vintage, 2-record set of 'bloopers' that

included it."

Other WOR Name Notables9

Two other WOR name notables in the early 1940s were Henry Morgan

and Cab Calloway. Morgan started as a WOR staff announcer in September

1940. As his dry wit caught on, he went national on the Mutual Network

with "Here's Morgan" that ended in the mid 1940s when

he entered wartime military service.

From July to September in 1941, WOR also aired Cab Calloway's

"Quizzicale" -- a showcase for the Calloway Band. It failed

to find a sponsor and was dropped.

Additions

From Mike Conway

|